Scientists have recently come close to creating the heaviest object ever

In a modern work of alchemy, scientists have used a spear of vaporized titanium to create one of the heaviest objects on Earth – and they think the new technique could pave the way to at higher altitudes.

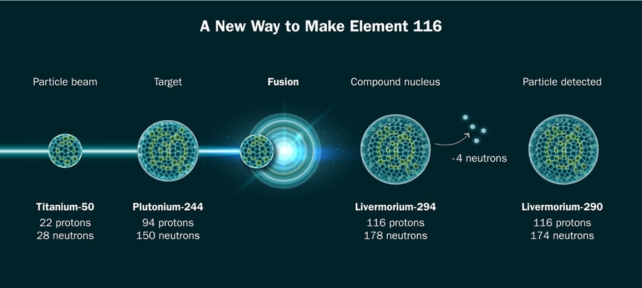

This is the first time that the new method – in which a hunk of the rare isotope titanium-50 is heated to about 1650°C (3000°F) to release irradiated ions from another substance – has succeeded in producing an object very heavy, livermorium. .

Livermorium was first made in 2000, and it is not the heaviest thing that people have made (that would be oganesson, atomic number 118).

So what’s the big deal if a few atoms of livermorium just appeared at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory – periodic table keepers might ask? Livermorium is ‘so Y2K’, and has only 116 protons.

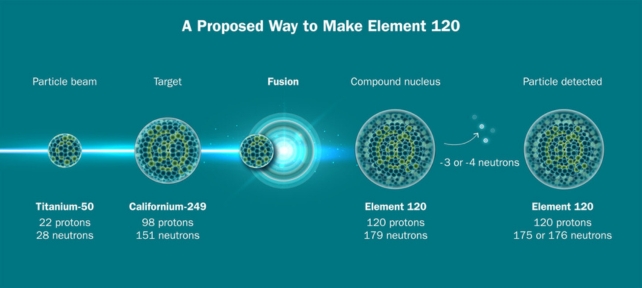

But combining titanium and plutonium to create livermorium is only an experiment for larger (or rather, heavier) objects. Scientists hope to create the heaviest element ever produced: unbinilium, which has 120 protons.

“This reaction had never been demonstrated before, and it was necessary to prove that it was possible before we started our efforts to make 120,” says the chemist nuclear physicist Jacklyn Gates of Berkeley Lab, who led the research.

Calcium-48, which has 20 protons, has always been the main one, because its ‘magic number’ of protons and neutrons makes it stable, helping it meet its target.

Titanium-50 isn’t ‘magic’, but it does have the 22 protons needed to reach atomic weight, without being so heavy that it just collapses.

“It was an important first step to try to make it easier than a new material to see if going from a calcium tree to titanium changes the speed at which we produce these parts,” the expert physicist Jennifer Pore of Berkeley Lab explains. .

“Creating part 116 in titanium confirms that this production method works and we can now plan our hunt for part 120.”

It took the team 22 days of work at Berkeley Lab’s 88-inch cyclotron, which accelerates heavy titanium ions into a tube powerful enough to fuse with its target. After all, it yielded only two measly atoms of livermorium.

Creating unbinilium this way, by targeting the bridge to californium-249, will be much faster than previous methods could provide, but it will still be noisy.

“We think it will take 10 times longer to make 120 than 116,” says Berkeley Lab nuclear physicist Reiner Kruecken.

This marks a return to a very tough race for the US Department of Energy’s Berkeley Lab, a leader in fundamental discovery in the 20th century.

Scientists around the world have been racing to produce unbinilium since at least 2006, when a Russian team at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research made the first attempt. Scientists at the GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion Research in Germany conducted several experiments between 2007 and 2012, but nothing.

Now, when researchers from the US, China and Russia are throwing their hats in the ring, one has to wonder what exactly the applications of the future might be.

frameborder = “0” allow = “accelerometer; autoplay; write to clipboard; encrypted media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web ratio” referrerpolicy=”start-hard-when-space” allowfullscreen>

“It is very important for the US to get back into this race, because the very heavy elements are very important in science,” nuclear physicist Witold Nazarewicz, who was not involved in the research, told Robert Service Science.

Element 120 is close to the ‘island of stability’, a paradise of very heavy elements where half-lives are long, thanks to their ‘magic numbers’ of protons and neutrons.

These long-lived, stable high-mass objects are expected to allow scientists to study the extreme behavior of atoms, test models of nuclear physics, and characterize the boundaries of atomic nuclei. .

This paper was published by Physical Examination Letters.

An earlier version of this article was published in August 2024.

#Scientists #close #creating #heaviest #object